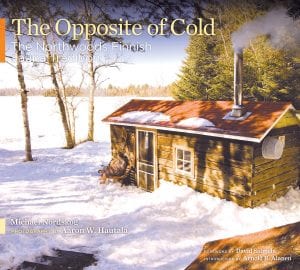

If you like history and saunas the two are combined in this awesome book, The Opposite of Cold. With beautiful pictures and intriguing text, this book will keep your interest piqued and at times, steam (not from a sauna) might start coming from your ears when you learn about the hard times and discrimination these early settlers suffered.

With pictures rich in color and more naked backsides than I’ve ever seen before, The Opposite of Cold—The Northwoods Finnish Sauna Tradition is an entertaining book, and will make a fine addition to display on your coffee table.

What fascinated me most was the rich history of North America’s Finnish people depicted in these 187 pages written by author Michael Nordskog, a Wisconsin attorney, writer, and editor who grew up in the heart of sauna country.

Photographer Aaron W. Haustella did an excellent job telling stories with his pictures, some funny, some poignant. Pictures were taken in Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota.

The first wave of Finns came in the 1630s and 1640s, “when they established the New Sweden colony along the Delaware River valley in what now forms parts of Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maryland.”

But like the mist from their saunas, they were absorbed into the culture, and it wasn’t until 1809 when Finns, now under Russian rule, would immigrate to America in a wave that lasted about 100 years. Many of them were drawn to land and water that reminded them of their homeland. Thus, these hardy souls moved to Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ontario, Canada.

Ninety percent of all Finnish farms had a sauna. In fact, the sauna was often the first structure built by the hard-working people. And make no mistake, Finns preferred farming to all other forms of work, no matter how tedious or poor the northern soil was.

In Minnesota the Iron Range was a hot spot for early Finnish settlers. Finns would work in the mines until they earned enough money to buy land or buy a farm. Once established on their property, they often quit the mines.

Other locations Finns found home included Cokato, New York Mills, Embarrass, and Esko in Minnesota; Oulu, Brantwood, and Marengo in Wisconsin; Calumet, Misery Bay, Neguanee, and Kiva in Michigan; and Ontario locations ranging from Thunder Bay to Sudbury.

One detail not mentioned in the book is that Thunder Bay has the largest Finnish population living in one location outside of Finland.

In Minnesota, in 1895, Finns became the largest ethnic group on the Iron Range. Bachelor Finnish loggers became known as Jack Pine Savages. Signs posted on taverns said, “No Indians or Finns allowed.” As recently as 1908, “a federal district court in Duluth had considered the issue of whether Finns were Mongols and thus ineligible for citizenship as a colored people under the

1882 immigration act, commonly known as the Chinese Exclusion

Act.”

In June of 1930, the Mesabi Range Finnish Workers Federation purchased land on a small springfed lake and built a children’s summer camp. The park was called the Mesabi Range Co-operative Park. The camp’s lakeside sauna survived into the 1960s and the “circumstances of its demise are only rumored.

“By the mid-1990s the park’s membership recognized that part of its heart was missing. While it could no longer be considered a Finnish cultural organization, the members realized that a lakeside north woods camp on a springfed lake without a sauna was a lost opportunity for fellowship.”

After building the new sauna, one of its noted features is “a thick cedar sauna door salvaged from a project at Lutsen Resort.”

So saunas became the backbone of the Finnish tradition. And despite early confusion by neighbors regarding Finns’ bathing habits—in Embarrass, Mn. the Finnish people were called “black Finns” because they would go to their saunas in white sheets and were thought to be witches—the tradition caught on for many non-Finns.

One of the featured steam baths still in existence is the Ely Steam Sauna, begun in 1915. It serves an array of customers from Boundary Waters canoe campers to Finnish American regulars.

All of the information about how to take saunas and the many variety of saunas available on the market is within these pages. The book is rich in tradition, and throughout, it speaks of a people who were independent, worked hard, and brought their skills and talents with them to America. The Opposite of Cold is one hot book. It’s informative and a lot of fun.

Loading Comments