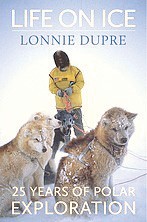

Like few people before him, Lonnie Dupre, of Grand Marais, captures the hardships and the heartwarming experiences or exploring the Arctic in his book, Life on Ice: 25 years of Arctic Exploration.

Lonnie Dupre was born for adventuring in the Arctic. His great-grandfather was 15th century explorer Jacques Cartier, who claimed the territory known as Quebec for the French. As a youngster Dupre’s father would take him into the wilderness from their farm and teach him about the animals, how to fish, how to hunt, how to survive.

At age 6, on a spear fishing trip with his father, their snowmobile fell through the ice and it was all his dad could do to get him home and warm him up before hypothermia set in. “Mom thawed my frozen snowsuit with warm water and tugged me out of it while dad held the cuffs. As my suit and I thawed, baby bullheads wriggled out of my pockets.”

He would sleep for 24 hours and two days later find himself back on the same lake with his brother Ted, following mink tracks. The fuse had been lit. The Arctic was calling him.

Bridge inBering expedition:

In Lonnie’s first expedition

1989, he joined with Paul Schurke and 10 others on joint Soviet-American Arctic expedition to promote peace. They traveled by dogsled through small Siberian villages after crossing the Bering Bridge, meeting the people and being their guests. Cold. When Dupre talks about 49 below zero getting to be “balmy,” you know he has come through some ferocious cold to get to that point. on wereDogs. Lonnie’s best friends some of these trips his sled dogs–the true heroes of the north. In these pages Lonnie’s depiction of the dogs and his relationship with them is often provocative and powerful. Energy/endurance. Over and over again Dupre and his colleague suffer from fatigue. On almost every page there is a test of endurance or a perceived shortage of energy. But he always makes it. Fahrenheit. Temperature, temperature, temperature. How warm or how cold it is determines how far dogs and men can travel. Other words that start with F that need mention are food and fire. The cold dictates that working men in the Arctic consume as much as 8,000 calories a day. And still they lose weight. When your fingers are too numb to light the cook stove or fix the heater that is leaking gas and asphyxiation is near. … As Dupre talks about near misses and his hunger while fighting the brutal cold, we realize that sometimes luck or fate (maybe the most important F word) is sometimes all that kept him and his partners alive. Greenland. Dupre recounts his trip to circumvent Greenland with teammate John Hoeschler. Help. No one can do all things by themselves, and Dupre gives full credit to all of the people who helped him and traveled with him on his 25 years of Arctic exploration. He also writes about the many times that no one could rescue him or his party if something should go awry. “If something goes wrong, there will be no one that can come and rescue us,” he muses as he sits floating on a thin raft of melting ice. fightingIce. Lonnie has spent 25 years sliding on it, gliding on it, it, falling through it, squinting at it, blinded by it, pushing through it in kayaks or pulling sleds and gear over mountains of it, melting it, falling on it, loving it and yes, at times, cursing it. Jon. Jon Nierenberg was part of Dupre’s first big trip, the 3,000-mile Northwest Passage. Along with them were Tom Viren and Malcolm Vance. After traveling 800 miles the team had lost 15 dogs, 10 of them Jon’s. Jon and Tom left the trip at that point and Lonnie and Malcolm traveled the remaining 2,200 miles to complete in reverse the epic journey of Roald Addmunsen in 1906. Kill. On Lonnie and his partner Eric Larsen’s “One World Expedition” the duo was attacked by a polar bear. “For the first time in my life I knew what it was to be prey….” Dupre chronicles in agonizing detail the bear’s charge and his and Eric’s retreat into the back of their tent as he fired shots at the bear.

“When we were sure he was dead, I lowered my head and wept. I had just killed the very animal we were trying to protect.” Leads. When on the 2006

“One World Expedition” expedition Lonnie and Eric Larsen came upon leads that were too large to get around, so they donned dry suits that allowed them to swim across and pull their gear. Mukluks. Originally created and worn by the arctic aboriginal people, this is what Arctic explorers wear, or their modern equivalent. Night. Lonnie spent months traveling through the long Arctic night. Oceans. Dupre argues that global warming is causing the polar ice cap and glaciers to melt. At book’s end, he writes, “As one of the last explorers to traverse the ever-thinning ice of the Arctic Ocean with any degree of solid-footing, I feel obligated to speak for this place of mystical light and dark, and for its people and its wildlife.” Pictures. The book has 32 pages of pictures. The pictures alone are worth the price of the book, which took 10 years to assemble and write with the help of editor Ann Ryan and his friend, retired Minneapolis Star-Tribune editor Jim Boyd, and many others. Questions. The book is filled with questions, some with no clear answers. Rugged. The people of the region and Arctic explorers must be rugged.

Greenland dogs can pull sleds that are 13.5 feet long, 34 inches wide and carry up to 1,000 pounds. Dupre’s dogs pulled sleds on long journeys of up to 3,000 miles that lasted six months or longer. Tough. Sweet as sugar,

Lonnie stands 5’7” and weighs 160 pounds, but few people have the endurance, skill or are tough enough to endure the hardships thrown Lonnie’s way by the Arctic. Uelen. While in Uelen a

17-year-old Russian girl begged Lonnie to hide her in his sled. She was desperate to leave the Soviet Union and come to the United States.” I told her it was impossible. “Of all the things that happened to Dupre on his five trips, he said leaving this girl in Russia was the hardest thing to do. Vision—Dupre’s vision for the health and welfare of the Arctic region, its people, plants, animals, and sea life is well stated. whatWillpower. More often than not, willpower is pulls Lonnie through. Xmarks the spot. When planes came to pick up Lonnie and his crewmates they would have to mark out a landing spot on the ice for the pilot to find and land on. Yukon Territory. Covering

207,076 miles with its largest city, Whitehorse, populated by 22,000 people, and next largest city at about 1,500 people, it is part of the long, lonely expanse covered by Dupre in his first expedition. Zzzz. Another word for sleep. After several days of travel, it wasn’t unusual for Dupre and the crew to rest for a day, or two. The energy it takes to move any distance in the Arctic is enormous, and rest is crucial.

The book tells so much more—of the Bering Bridge Expedition in 1989; of the Northwest Passage Expedition in 1991-1992; followed in 1997-2001 by the Greenland Expedition. Next, the One World Expedition in 2005- 2006 and finally, the 2009 Peary-Henson Centennial Expedition.

The ABCs of life on the ice and more.

Loading Comments