Like many veterans, Kenny Lovaas of Grand Marais doesn’t talk much about his military service. He graciously—but reluctantly—agreed to an interview the day before he joined the Northland Honor Flight on its trek to Washington, D.C. to see the memorials honoring our nation’s veterans.

The News-Herald asked Lovaas if it is painful to remember his tour of duty in Korea and Japan. He said no. “It’s like a dream in a way,” he said.

Lovaas said he doesn’t remember all the details, such as the location of the induction center he reported to in the Twin Cities. He does remember basic training at Fort Riley, Kansas though. When he was done, his military occupation specialty (MOS) was infantry.

After basic training, he had a seven-day leave. He used it to travel to the North Shore to marry his sweetheart, Fern Shold. And then it was off to Korea.

Lovaas had his first plane ride to the West Coast, where he was put aboard ship for the voyage to Japan. It took 11 days. He spent only a few days in Japan before he was ordered aboard another plane—a DC3 with no windows and hammock seats—to Seoul, Korea.

Lovaas said the countryside was devastated. “The war started in 1950. I got there in 1951. North Korea had driven all the way down to Seoul. When I got there, there was nothing left. No bridges or roads,” Lovaas remembers.

When he arrived in Korea, he was ordered to roll call. “You stand in line, waiting for your name to be called,” said Lovaas, noting that when his name was called, he was ordered into the back of a 2½-ton truck (a deuce and a half) and hauled to the front line. “I had no clue where I was going,” explained Lovaas. “I just followed along.”

He ended up north of the 38th Parallel, the dividing line between North and South Korea in the village of Kumwha, North Korea. The village was as damaged as Seoul, the landscape pocked with bomb craters. “Kumwha wasn’t really a town. There wasn’t anything left of it when I got there. The saddest thing was the old people and the kids running away—they had nowhere to go.”

Lovaas was assigned to the 77th Field Artillery, 1st Cavalry, where he was met by a captain demanding to know what he—an infantry man— was doing in an artillery unit. Lovaas smiles at the captain’s frustration and reiterated, “I just went where they told me to go.”

Eventually they realized that Lovaas had worked in a garage. He was assigned to the motor section. Despite his experience as a mechanic, he said it wasn’t a pleasant job. “You’re right there with the artillery,” he said.

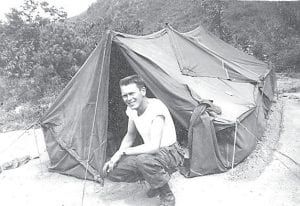

In the camp, they lived in tents and improvised shelters. He said he and a buddy took ammo boxes, filled them with sand and stacked them, then crafted a canvas roof, providing some protection from small arms fire.

It wasn’t that the enemy had a lot of fire power, he recalled. It was just that Chinese soldiers were fighting alongside the North Koreans. “The Chinese didn’t have a lot of artillery— just a lot of people—they just overran us with people,” said Lovaas.

The enemy also employed land mines. Lovaas remembers a Jeep from his unit being destroyed by hitting a land mine. “There was a place to shower set up by the river. You didn’t walk across the field. You used the road,” he said.

Lovaas also recalled, “All our equipment was junk, leftover WWII equipment.”

He remembers an equipment failure that nearly cost him a finger. He was traveling with a group of soldiers in a Dodge weapons carrier when the axle shaft broke. In the sweltering August weather, repairs had to be made on the roadside. As the old shaft was being removed to put a new shaft in, his coworker made an unexpected turn of the shaft, clipping off the end of Lovaas’s finger. Lovaas passed out from the pain and the heat, waking up to see a medic leaning over him, cigarette dangling from his lip, applying smelling salts.

Lovaas was loaded into an ambulance and taken to a field hospital, a nightmarish place. “I sat there for about an hour, watching choppers coming in, bringing in guys that were mangled. I said, ‘Give me a Band-Aid and let me outa here.’”

A horrible memory, yes, said Lovaas, adding, “It’s just war time. It’s the way it is.”

One of the hardest parts of the tour was being away from his new bride. He can vividly recall the points system. He said troops had to accumulate a certain amount of points to get home. Four points a month were allotted in combat. Once a soldier earned enough points, he earned some R&R or got to go home. “Near the end of November, I was getting pretty close to the end of my points. You needed 24. It was Thanksgiving Day— they promised us a hot turkey dinner. We got turkey, but it wasn’t hot,” he said.

During that cold turkey dinner, Lovaas got word that the points needed to return to the United States had been upped to 36.

He was discouraged, but for some reason, the 1st Cavalry Division was pulled out of Korea shortly after that, to Japan. As motor sergeant, he was part of the advance party sent to Japan. He spent the rest of his time in the service inventorying equipment. He was surprised at the reception of the Japanese people and the state of that country. “It was only five years after the end of WWII, and the Japanese were wonderful, happy people,” he said.

Lovaas said he didn’t think about his time in Korea much for many years. He came home from Korea, to the North Shore and Fern. He went to work at the Shold & Lovaas Service Station for 39 years and drove school bus for 44 years. He and Fern raised their family.

In 2000, he received a special letter of appreciation from Kim Daejung, president of the Republic of South Korea, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the truce that halted. hostilities “I started thinking about it a little bit more,” he said.

Asked if he would recommend military service to a young person today, Lovaas said he isn’t sure. “I don’t know; it’s different now.”

“But long story short— was it worth it?” said Lovaas. “When you look at South Korea today –they are a thriving country. They never would have had that, if we hadn’t been there.”

Loading Comments