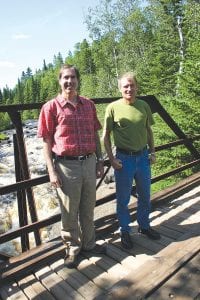

Questions have been raised about risks to the fish population of the 23-mile-long Poplar River after the state legislature authorized an increase in the amount of water Lutsen Mountains can take from the river for snowmaking each winter. This view is where the upper 20.4 miles, which holds most of the river’s fish population, meets the steep portion running through the ski area and down into Lake Superior.

All streams flow into the sea, yet the sea is never full.

That’s one thing King Solomon, the biblical ruler known for his wisdom, had to say about the way nature tends to keep itself balanced. It’s too bad we can’t ask him how much we should worry about extracting water from the Poplar River just before it empties into Lake Superior.

The issue came up this spring when Senator Tom Bakk and Representative David Dill successfully introduced a bill allowing Lutsen Mountains to extract up to 150 million gallons of water a year from the Poplar River in order to make snow. Lutsen Mountains co-owners Charles Skinner and Tom Rider requested the legislation to meet the demands of a very competitive industry that makes a significant contribution to the economy of Cook County, bringing tourist dollars and keeping residents employed through the winter months.

Some people have expressed concern over how taking water from the 23-mile-long Poplar River—one of Cook County’s 84 designated trout streams—might affect the fish population.

Lutsen Mountains co-owners Tom Rider (left) and Charles Skinner on the bridge over the waterfall 2.6 miles from the river’s mouth.

The portion that would be most affected is a pool about five feet deep in the 400 feet below the lowest falls, just before the river reaches Lake Superior. The 20.4 miles of river north of the second set of falls just above the ski area represent the majority of fish habitat for the river.

“The percentage of the river’s fish living below the lower falls is low, and the river itself is just a small part of the North Shore ecosystem,” DNR Area Fisheries Manager Steve Persons of the Grand Marais office told the Cook County News-Herald. “In fact, all parts of the North Shore ecosystem, in and of themselves, tend to be small, and the loss of one or two of these small parts, by itself, tends to have little effect. However, in environmental issues we try to prevent the loss of as many of these small parts as we can, because if we lose enough of them, we can lose the whole system.”

Increase in need for water

The ski area’s need for water to make snow has increased over the years, with wider ski runs to accommodate the larger turning radius of modern skis, the addition of snowboarding features, a trend toward taking ski vacations later into the winter season, and the expectations of modern skiers who might not return if runs did not have a good base and complete snow cover.

Lutsen Mountains upgraded its water monitoring equipment about 10 years ago and found, with more accurate measuring equipment, that it was extracting more than its permit allowed. The business has been reporting the amounts it has taken each year and has been working with the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) ever since to obtain permission to continue to get what it needs for making snow.

Lutsen Mountains’ first permit was granted in 1964, when it was authorized to take 9.6 million gallons a year from the river. In 1977 a new law prohibited anything but temporary extraction of water from Minnesota’s designated trout streams, but Lutsen Mountains’ permit was grandfathered in and it was allowed to continue extracting water as usual. In 1986 the resort’s permit was amended to allow the extraction of 12.6 million gallons a year.

“The ski and tourism businesses are very competitive,” Rider said. “The costs of running a ski resort have increased far more than the rate of inflation. Nearly half of the ski areas that existed in 1980 have gone out of business. You can either keep up or become extinct.”

Lutsen Mountains needs a base of three feet of packed snow to operate, and it tries very hard to lay this base by Christmas each year. In an average year, one foot of the packed base is provided by natural snowfall and the other two feet come from snowmaking. The water level in the river gets lower as winter progresses and things ice up, but the ski resort usually gets two-thirds of the water it needs between November 1 and Christmas, before water levels are at their lowest.

“We are continuing to invest in snowmaking infrastructure that will enable most or all of our snowmaking to occur in November and December and reduce or eliminate snowmaking in January and early February,” a June 28 news release from coowners Charles Skinner and Tom Rider states.

The impact of extracting water

“We can’t say with any certainty how the withdrawal has affected the trout population,” said DNR Area Fisheries Manager Steve Persons of the Grand Marais office. “That stretch of the river should be capable of supporting more trout than it does now, based on what we see in similar streams along the North Shore.”

Nobody knows how many fish lived in the lower Poplar River before snowmaking began, but other factors are believed to have impacted the fish population as well, such as the sediment that has caused the river to be designated an impaired waterway by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA).

Data on the amount of water flowing down the Poplar River was collected by the U.S. Geological Survey from 1911 to 1961. The amount of water Lutsen Mountains extracted this last season, its highest amount ever, was 108 million gallons, which is 2.5 percent of the average flow from November through February, when the resort makes its snow. The maximum allowable amount of 150 million gallons per season would represent 3.5 percent of the 50-year average flow during those months.

Brook trout eggs laid in the fall “require constant flows of oxygenated water,” Persons said, “and can easily be killed by the formation of ice. Ice formation is most widespread when flows are low and snow cover is also low – conditions under which a withdrawal for snowmaking is likely to be high…. In cases where rivers have frozen solid (and this has happened twice in this area since 2000), trout populations have been decimated, if not completely eliminated. Recovery, where it has happened, has taken many years.” Persons said juvenile steelhead also suffer when water levels get too low in the wintertime.

The legislation passed this spring, however, prohibits extraction when the river’s flow becomes lower than 15 cubic feet per second (cfs). The month with the lowest flow, February, averaged 30 cubic feet per second between 1911 and 1961.

“If that regulation was followed and enforced (so that pumping absolutely ceased at that flow level, and did not resume until flows improved), fish and eggs would have some protection,” Persons said. “A withdrawal upstream will reduce flows near the mouth and increase the chances that the pool (and more importantly, gravel beds in the reach) would freeze.

“We do not know whether the 15 cfs protected flow will serve as an effective control on the appropriation, or if it is enough to ensure the continued health of aquatic resources dependent on that section of the stream. The question to be resolved in the long run is whether or not preventing damage to aquatic resources in this stretch of river is worth the cost of requiring Lutsen Mountain to shift to a different water source for snow making.

“To be effective,” Persons continued, “the protected flow has to be complied with and enforced. If that happens, I would be less worried about the appropriation. However, it still sets a dangerous precedent by opening the door to appropriations from trout streams all across the state.”

From here on forward

Rider and Skinner support research on how much water needs to be in the lower 2.6 miles of the river to sustain a healthy fish population. In their news release they state, “We, of course, would take any evidence of true harm very seriously and seek solutions that safeguarded the fisheries.”

If the new authorization turns out to put Poplar River fish at risk, the ski area could bury pipes all the way to Lake Superior and draw its water from there. Lutsen Mountains’ neighbors have granted the easements they would need to do it, but at a cost of $3-4 million for infrastructure plus the cost of operation and maintenance. Another possibility would be to pump water from the lake into the lower 400 feet of the river to ensure that water levels remain high enough to sustain the fish wintering there.

The DNR must weigh various factors in determining how to manage the state’s land and water. According to DNR Area Hydrologist Cliff Bentley of the Two Harbors office, “The DNR works with citizens to conserve and manage the state’s natural resources to provide outdoor recreation opportunities and to provide for commercial uses of natural resources in a way that creates a sustainable quality of life.”

“Real people have concerns about the continued health of aquatic resources on the North Shore, just as real people have a stake in the economic health of the area,” said Persons. “I think that the concerns of both groups could be addressed by shifting this appropriation to Lake Superior, and I hope that we’ll get there someday.”

“Much of the ski area’s draw as a tourist destination depends on a pristine and healthy environment,” said Skinner and Rider, “and this dramatic mountain stream is enjoyed by tens of thousands of skiers each winter. Lutsen Mountains wants to continue to do its part to protect and enhance the Poplar River, including its fisheries. … In the meantime, we are working to promote a better understanding of the issues and explore new and better ways of achieving everyone’s goals. Good solutions don’t have to be win-lose.” In this case, they are hoping everyone wins.

Loading Comments