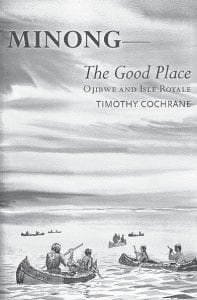

Tim Cochrane is a brave and ambitious man. For close to 35 years he has been collecting information from historical documents and people with stories to tell about the history of the North Shore Ojibwe on Isle Royale, and the book he produced, Minong—The Good Place: Ojibwe and Isle Royale, has now been published by Michigan State University Press.

The scope of Cochrane’s research is amazing, ranging from Ojibwe oral narratives, Jesuit records and diaries, and reports from the Hudson’s Bay post at Fort William to regional newspaper accounts and governmental archives.

What makes Cochrane so brave? Not only has he, a white man, tried to set the facts straight on the historical, economic, and religious significance of Isle Royale (known to the Ojibwe as Minong) to the North Shore Ojibwe, he, a National Park System supervisor at Grand Portage National Monument, has dared to suggest that the National Park System’s lack of understanding of Minong’s significance to the Ojibwe has been detrimental to this area’s native people.

On June 13, 2009, Cochrane read from and discussed his work at Drury Lane Books in Grand Marais. Cochrane holds a Ph.D. in folklore and said he has a keen interest in how wild places impact what people talk about, whether they are loggers, commercial fishermen, or U.S. Forest Service rangers. Getting the information he needed for this book, which he considers a blend of anthropology and history, “took a lot of detective work,” he said.

One of Cochrane’s sources was a set of diaries, letters, and other documents produced by three Jesuit priests living at Pigeon River in the mid-1800’s. Theyproduced – in French – up to 8,000 pages of detailed information about the ancestors of people living in Grand Portage today. While that source helped him understand Indian perspectives on the Treaty of 1854, from which the North Shore Ojibwe were excluded but which resulted in significant ramifications for them, the Jesuit writings did not necessarily reflect an understanding of other Indian perspectives. The Jesuits sent annual reports all the way to the Vatican, where, Cochrane believes, they could probably be found to this day.

Ojibwe narrative called Minong a “floating island,” possibly a symbolic spiritual reference to Minong being a raft providing safe refuge from The Great Flood or a poetic description of how the island looks when the lake is shrouded in mist. White interpretation of Ojibwe narratives about the “floating island” morphed into an assertion that the Ojibwe were afraid of Minong and did not use it. Cochrane cites a 1932 radio address which underscored the attitude that Isle Royale was there for the taking by whites moving in: “The island…was not properly anchored; when the wind blew from the north it floated across to the Keeweenaw, and when the south wind came, it drifted back to be near the Sleeping Giant on Thunder Bay. An island with such disgusting habits was no place for an Ojibwe, who likes his terra very firma, so Uncle Sam was very welcome to it.”

The speaker was wrong about Minong’s importance to the Ojibwe, however, Cochrane says. North Shore Ojibwe did travel to Minong. In addition to its place in spiritual narratives that refer to Mishipizheu, a powerful spirit being with a serpentlike tail of copper that controlled the waters, and Nanabushu, a spirit being both “wise and foolish…a taboo breaker and life giver,” Minong was a source of sustenance from fish, passenger pigeons, seagull eggs, berries and other plants, caribou, beaver, otter, snowshoe hares, and maple sugar.

Cochrane outlines how the coming of whites, creation of the international border, and division of land into private properties affected the Ojibwe. Treaties did not represent mutual understandings about land rights (including Isle Royale), and the North Shore Ojibwe did not receive fair compensation when the United States government established property boundaries. A Keeweenaw chief stated through an interpreter in the mid- 1800s, “…We deny selling Isle Royale…. The island belongs to the Indians living nearest to it [the Grand Portage delegation present when these comments were made].”

As industries emerged and changed, North Shore Ojibwe found employment on Minong in many ways as miners, fishermen, deckhands, loggers, lighthouse keepers, mail carriers,

and lodge employees. The transition from a nomadic lifestyle brought serious poverty to the Ojibwe, however. Not only did they lose access to historic hunting grounds and maple sugaring stands, but they lost out in other ways, such as when they had to travel to distant locations to collect treaty payments during the wild rice harvesting season.

“Through time,” Cochrane writes, “the Ojibwe storytelling idea that was most belittled and misunderstood was Minong as a floating island. Interpreted literally, it struck most whites as so preposterous that it was used to condemn Ojibwe as superstitious. The unvoiced notion being that if Ojibwe held such fantastical notions about the island, then surely they did not know much about it. From the proposition that Ojibwe did not know about Minong, it is an easy step to concluding they could not be its owner – ‘ownership’ as defined by whites.

“And yet, turning the concept around, it becomes very useful to summarize the North Shore Ojibwe’s relationship with Minong through time. Up until now, Minong has floated away from the Ojibwe in a legal, economic, and historic sense. Even today’s highway maps ‘cut and paste’ Isle Royale in a convenient blank map space in Lake Superior, closer to the South Shore. Taken literally, these maps mislocate Isle Royale – essentially ‘floating’ in Lake Superior, rather than in its proper location. It is almost as if its real location does not matter.”

“There are, however, resilient Ojibwe experiences and values connected to Minong,” Cochrane says. The Grand Portage band remains involved, with its marina being the American port closest to Isle Royale, its knowledge of Lake Superior fish, and an interest in the economic potential of tourism at Minong.

“Minong is now starting to float back closer to the orbit of North Shore Ojibwe,” Cochrane concludes. “The National Park Service recognizes the Grand Portage Band as an important player in the overall experience of park visitors, and as uniquely interested in management of the island. Perhaps with Minong being a little bit closer to the North Shore, there will be greater possibilities for understanding its past and guiding it towards bright future.

“…Visible from many Portage living rooms, it looms on the horizon of the lake. Future efforts by Grand Portage residents may yet have it float closer to home.”

Minong—The Good Place: Ojibwe and Isle Royale can be found in Cook County at Drury Lane Books, the Lake Superior Trading Post, Birch Bark Gallery, and the Grand Portage National Monument.

Other books published by Cochrane are A Good Boat Speaks for Itself: Isle Royale Fishermen and Their Boats (by Tim Cochrane and Hawk Tolson) and Borealis: An Isle Royale Potpourri.

Loading Comments