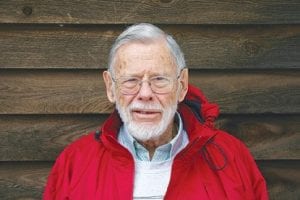

Although Lyle Gerard of Grand Marais appreciated the honor of being among the 89 veterans taking part in the Northland Honor Flight in October, the experience also resurrected many painful memories of his time in the service.

Gerard spoke to the Cook County News-Herald about his time in the Army infantry, which started with induction at Fort Snelling and basic training at Camp McClellan, Alabama. When his Army entrance scores were tallied, his test results were high enough for him to be sent on to college at the South Dakota School of Mining and Technology in Rapid City, South Dakota. “Engineers were in great demand,” said Gerard.

He enjoyed college and made some good friends there, “a wonderful group of five guys,” recalled Gerard.

Unfortunately the time was all too short. After just five months, Gerard and his buddies were called to duty with the 44th Division and Gerard was assigned to the 324th Infantry Division, which set sail from the Boston Port of Embarkation to France and ultimately Germany. “It didn’t matter what your job was, or what your rank was, you were infantry,” said Gerard. “It was very unfair— master sergeants were demoted to sergeant first class or lower. The rest of us were buck privates.”

“It was an eye-opening experience for a young man,” said Gerard—and difficult. He was shocked to encounter discrimination from the roughand tumble unit that was made up primarily of East Coast soldiers. “I was immediately dubbed ‘Chief’ because I was from Minnesota and for some reason they thought everyone from Minnesota must be Indian,” said Gerard, who is not Native American. He was also denigrated because of his education. “’College kid, get your ass over here,’ was a favorite command,” recalled Gerard.

He said he quickly learned the military pecking order and that an acting corporal outranks a buck private. A corporal once ordered him to pick up cigarette butts. Since he didn’t smoke, Gerard said no—and spent hours cleaning out the camp kitchen grease traps. Another time he was listening to a sergeant with a thick New York accent chewing out his troops. Since he couldn’t understand what the sergeant was saying, he started smiling—and found himself scheduled for four hours of marching up and down the street in full military gear.

There was one leader that Gerard said had “a rough kind of fairness,” Sergeant Fitzpatrick. Gerard shudders as he recalls that he got “cooties” after sleeping in a spot where the German Army had just departed. Suffering, he went to “Sgt. Fitz” and reported the problem. He learned he was to be sent to the town of Nancy, where he would be treated [by entering a room filled with DDT], given a hot shower, clean clothes and a hot meal. In return for the break from battle, Sgt. Fitz handed him a Shinola (shoe polish) container. “I asked why?’ and Sgt. Fitz said, ‘Don’t you want the other guys to have the same chance? Bring back some cooties,’” said Gerard.

With such drastic measures to get time away from the front, it is no wonder that Gerard fondly remembers receiving Red Cross packages. Gerard was one of the few soldiers who didn’t start smoking the free cigarettes that came in the Red Cross packages and with C-rations. He was able to stockpile his tobacco and trade it for chocolate. Of the Red Cross packages, Gerard declares, “Every package had toilet paper, cigarettes and chocolate—they were gifts from heaven!”

At one point Gerard’s unit held the record for the most days on the “front line.” Gerard said the front line is nebulous. “We were never in deep, deep combat but we lost someone every day,” he said. One of the first casualties was one of his close friends from college in South Dakota. Another friend died when he was hit by a mortar shell. He didn’t die immediately, but no one could go to his aid. The battle-worn sergeants told the new recruits that if a group congregated around the wounded man, they would send another mortar shell. “Don’t you dare go help,” they were ordered.

Discrimination, unsanitary conditions and the constant threat of being killed were bad enough, but Gerard was appalled at the behavior of his fellow American soldiers. At the end of the war, Gerard said, the Germans were getting desperate. “We were fighting the ‘ulcer division’—old men and boys,” said Gerard, noting that U.S. soldiers treated them with unnecessary cruelty.

“All this glory and hubbub, victory flights and so forth—to me they represent that we have been a very militaristic nation for over a century. Anytime there is a gathering of power, there is a chance for someone to take advantage of it,” said Gerard sadly.

Gerard was able to strike a subtle blow at the system when the Army sent an 18-year-old Jewish boy from Poland to Gerard’s unit as a “replacement.” Gerard said replacement soldiers typically did not last long. They did not learn the skill of avoiding incoming mortar shells—knowing which sound signaled keep walking and which sound signaled hit the dirt—fast enough and they were lost at alarming rates. So when the young man’s gun suddenly went off, injuring his hand, Gerard did not question the “accident,” knowing the replacement would be sent away from the battlefield. Gerard felt he had saved one life.

Some of his happiest—and saddest— memories are of his friend Frank DeMayo. Gerard and DeMayo hit it off. They were both scholars and uncomfortable with the military. In fact, Gerard smiles as he describes his friend. “He was fat, flat-footed and couldn’t see very well. How the hell he got in the Army, I will never know,” said Gerard.

DeMayo saved Gerard’s life on one of the first days they met. They were fighting and as the bombardment got close, DeMayo would knock Gerard into a hole and fall on top of him. Gerard pointed out that it wasn’t fair for DeMayo to always protect him. His friend laughed and said that the tall and skinny Gerard would be no protection for him.

The men became bosom buddies and traveled together as much as possible until the day DeMayo was killed. Their unit had been advancing on German forces when a medic told Gerard that another friend, a buddy from Brownsville, MN had been injured and needed to be carried back. Gerard helped get him back and because there were many other wounded men, he was pressed into service there. It wasn’t until late that evening that he learned that after he left, Frank DeMayo had been killed.

Gerard said his gunner, a man named McAdoo, had been captured. Gerard said that he was a bazooka man and he likely would not have survived the day. But that didn’t make the loss any less painful. Gerard somehow made it through another year and was discharged on December 17, 1945.

After getting out of the Army, he attended Duluth Junior College and worked on a ship on the Great Lakes as a coal passer for a year. He went on to Macalester College and then the University of Minnesota, earning his degree in education, speech and drama. He met and married Joan Woolsey in 1950 and together they raised three daughters. Gerard was a Fulbright teacher in Holland in 1958- 59 and taught school in St. Louis Park for 36½ years. Lyle and Joan eventually moved to Lutsen where they lived until Joan’s passing in 2007.

Gerard is known to many as “Grandpa Lyle.” You may have seen him reading to school children or to residents at the Care Center. He is involved in a number of community activities and has done all he can to keep the memory of his friend Frank DeMayo alive, through various charitable donations in his name.

Gerard insists, when you talk to him about his experience in World War II, “I’m no hero.”

To which this reporter—and likely all who know him— would disagree. To make it through the horror of war as he did, to continue to honor his fallen friend, and to live each day as he does, in service to others, is what makes Lyle Gerard a hero.

Loading Comments