The U.S. Forest Service (USFS) has a lot of decisions to make about managing the forest. Every year, Superior National Forest Gunflint District personnel take a certain portion of the forest and analyze what could be done to keep it healthy and make it the type of forest people want to use and enjoy. The Forest Service could legitimately take many different directions, and one of its directives is to take into consideration what citizens want to see in the forest.

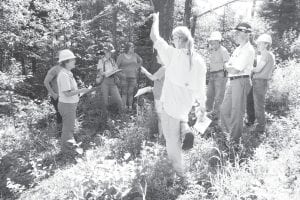

Toward this end, District Ranger Dennis Neitzke and five staff members with different specialties offered a tour on July 18 of three different areas in the current vegetative management planning area that falls between the Lima Grade Road and Greenwood Lake. It is called the Lima Green Project.

The Forest Service has several objectives for the project. One is to improve moose habitat, a desirable goal as the moose population has been mysteriously declining in northeastern Minnesota. Another objective is to restore red and white pine for its scenic beauty, the habitat it provides for many wildlife species, and the timber it can produce. A third objective is to enhance the long-term scenic quality of the Gunflint Trail.

A collection of people including Gunflint Trail Scenic Byway committee members, Cook County ATV Club members, local news reporters, a private forest management contractor, a retired USFS Gunflint District employee, and a St. Olaf professor on sabbatical gathered on a hot and slightly buggy day about 12 miles up the Gunflint Trail. Ranger Neitzke introduced the focus for the day.

“We have a forest that’s 100 years old,” Neitzke said. Much of it is dying, and the area has seen a lot of fires and blowdowns in recent years. The new understory that is coming in naturally is largely balsam fir, hazel (a shrubby tree), and aspen. Neitzke invited the group to offer their input on what they wanted this area of the forest to look like in future generations.

Staff members Myra Theimer, a silviculturist, Melissa Grover, a biologist, Patty Johnson, a fuels specialist, Heather Jensen, a monitoring specialist, and Becky Bartol, a planning specialist, guided the guests through three different areas along the Gunflint Trail and talked about options for managing them.

Maintaining the Scenic Byway

The first area was a 116-yearold jack pine stand being replaced naturally by balsam fir. A description of the project states, “Within five to 15 years the mature jack pine will die and fall down and balsam fir regeneration will increase in the understory. Without disturbance, jack pine, a necessary component of the ecosystem, will be replaced by balsam fir. The dead jack pine and young balsam fir create a high fuel load along the Gunflint Trail.” This is significant because the Gunflint Trail is the only way out of the woods for a lot of residents and visitors living northwest of this area.

The proposed treatment is to clearcut patches to allow enough sunlight to allow the jack pine to regenerate. The group discussed whether to leave a vegetative buffer alongside the Gunflint Trail, which Myra Theimer wasn’t very enthusiastic about, or to cut alongside the road in patches. “I’m not a big fan of buffer strips because they can blow over,” she said.

Some clearcutting needs to be done to encourage jack pine regeneration, Theimer said. This can replicate fire, which burns up duff and releases seeds. “Jack Pine really is a very sun-loving species,” she said. When it has optimal growing conditions, jack pine grows fairly quickly.

Encouraging the growth of certain species takes intentionality, especially when species like aspen take over quickly and easily.

Another species that tends to take over is balsam fir, which burns very easily. The Forest Services tries to break up the continuity of balsam in order to keep fires from spreading. Natural fires used to clear out balsam and make room for red and white pine, Neitzke said, but when America started fighting forest fires about 100 years ago, the balsam began to crowd out other species.

Spruce budworm will eventually kill off balsam trees, but if they don’t get cleared out when they are young, they will die off and become even more of a fuel hazard. Interestingly, the spruce budworm rotation used to be about 40 years, but it has inexplicably decreased to a 20-30-year rotation.

Prescribed burns

The second part of the tour was beside an old CCC camp where a large field offers a landing pad for helicopters during forest fires. Patty Johnson explained that the jack pine are dying in this area as well.

The Forest Service is considering thinning the area by hand— leaving any trees over five inches in diameter—and burning the materials that are cleared after they’ve had a chance to dry for about a year. This is quite expensive, she said, but they do it because they can be more selective in what they clear out.

The description of proposed understory fuels reduction areas states, “All overstory trees would remain intact and all white pine, red pine, spruce, cedar and tamarack in the understory would be retained. …The distance between each treatment area would be at least 1,000 feet. Treatment boundaries would be irregular and not have straight lines. White pine or other conifer species would be planted in some of the areas.”

A lot of the plants in this forest are adapted to fire, Melissa Grover said, germinating only after a fire and growing only in areas that are open enough for a good deal of sunlight to get to them. Some seeds remain dormant in the ground for a couple hundred years, she said. This is called a “seed bank.” Blowdowns also help some of these species to grow, with fallen trees exposing the seeds and open areas bringing them the light and rain they need.

Encouraging white pine

The last tour spot was far down a very bumpy logging road. This area has a lot of white pine with hazel growing underneath it. Forest Service personnel are seeing root rot in some of the old trees.

An underburn was conducted in 1997, with a plan to follow up with a second burn the following year. The second burn didn’t have enough fuel to complete the job, and the 1999 blowdown resulted in resources being diverted to blowdown recovery efforts in other areas.

The science of prescribed burning continues to improve, Myra Theimer told the group, and much more is known today than they knew back in 1997. The plan for this area is to prepare the site by mechanically cutting down some of the underbrush, letting it dry, and then burning it. “It’s a great opportunity for us to reintroduce fire to the area,” Theimer said. They have to be careful how much is cut down, however, so the fire doesn’t get too hot and hurt the big trees. They have to burn on the right day, at the right time, and in the right conditions.

Mechanical preparation could include cutting underbrush with chain saws, mowing it down with special mowers, or bringing in bulldozers during the winter months. They want to disturb the soil to a certain degree (called “scarification”) and burn the mulch so that seeds will germinate.

The Forest Service has planted more red pine than white pine in the past because red pine was easier to manage. They have learned a lot in recent years about how to successfully grow white pine, however. “It’s expensive to try and get white pine back on the landscape,” said Patty Johnson. The goal is to get white and red pine stands back where they used to be, but their success in many areas won’t be known for 30 years, Theimer said.

A partnership

At the end of the tour, Ranger Neitzke said, “I have no interest at all in just saying, ‘Here’s what we’re going to do. It’s a partnership.’” Almost every project has been modified because of comments and information the Forest Service received from members of the public, he said.

Comments are being accepted until August 12 and can be submitted to District Ranger Dennis Neitzke, Attention: Lima Green Project, Gunflint Ranger District, 2020 West Highway 61, Grand Marais, MN 55604. They can also be faxed to (218)387- 3246 or emailed to commentseastern superior- gunflint@ fs.fed.us. Comments should include the sender’s name and address.

Questions on the project can be directed to Project Leader Becky Bartol at (218) 387-3207.

Loading Comments