Sworn to secrecy about his wartime activities, Lex Porter kept his word to the U.S. government. It was just this fall that Lex Porter’s family learned that he was a member of the famed Military Code Talkers in World War II. The family learned of Lex’s historic role when they received an invitation to Washington, D.C. to accept a posthumous Congressional Medal of Honor for his service.

Attending the ceremony at Emancipation Hall in the U.S. Capitol on Wednesday, November 20, 2013, were many family members— Lex’s children Joe Porter and Vivian Carlson of Grand Portage, his grandchildren Freedom Porter of Baxter, Minn., Allison Porter of Mille Lacs Reservation, Christine Porter of Grand Portage, Eric and Emma Carlson of Grand Portage, and Adrian Porter of Black River, Wis. And watching a live video feed back home in Grand Portage were dozens of people at the Heritage Center at Grand Portage National Monument.

At the ceremony, led by Speaker of the House John Boehner, the history of the Military Code Talkers was shared. Guests heard that the United States first used Native American code talkers during World War I in October 1918, when the country used Choctaws to transmit messages confounding to the Germans. The idea was reborn during World War II, when the Marine Corps recruited several hundred Navajos to serve in the Pacific. The Army used Comanches to develop a secret code based on their language, while members of other tribes were assigned to special native language communication duty.

U.S. Department of Defense estimates place the number of Native American code talkers who served in the two wars at more than 400. The code talkers’ role was kept classified until 1968. Those heroes—250 of them, from 33 tribes—were finally recognized, most of them posthumously.

“They returned heroes, but without a hero’s welcome,” said Rep. Ron Kind (D-Wis.), who co-sponsored the 2008 legislation authorizing the creation of the medals. At the November 20 ceremony, Kind credited code talkers for saving countless lives by being able to use their native languages to transmit in seconds secret battlefield messages that would have taken a coding machine at least 30 minutes to send.

During the ceremony, Navy Admiral James A. Winnefeld, Jr., vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said, “During Native American Heritage Month, I have the great privilege of representing the finest military in the world in recognizing hundreds of Native Americans who wore the cloth of our nation in the distinctive way we celebrate today, and in such a courageous way, defending a country that did not always keep its word to their ancestors.”

Admiral Winnefeld noted that throughout history, military leaders had sought the perfect code. “It was our code talkers who created voice codes that defied decoding. Our code talkers’ role in combat required intelligence, adaptability, grace under pressure, and bravery—key attributes handed down by their ancestors,” the admiral said.

Lex’s grandson, Freedom Porter, said the family knew that Lex had served in the Army during World War II. They knew that he was one of many Native American men who enlisted on December 8, 1941, the day after the horrific attack on Pearl Harbor. Freedom Porter remembers his grandmother telling him that most of the men from Grand Portage left that day, heading to Fort Snelling to enlist.

The family also knew that Lex, who passed away in 1990, served in the Pacific Theater, but most didn’t learn about his role as a Military Code Talker until they received the invitation to Washington in September. “He said he was a radio man,” said Freedom Porter in a phone conversation a few days after the ceremony. “He didn’t lie!”

Just before the Congressional Medal of Honor ceremony at the U.S. Capitol, Lex’s son Joe Porter admitted to the family that Lex had told him long ago about his service as a Military Code Talker. But Joe respected his father’s wishes and also kept it a secret.

So it seems fitting that Joe Porter will be the keeper of the silver replica of his father’s Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor for an individual serving in the Armed Forces. The Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, of which Lex was an enrolled member, received the gold medal. Accepting the stunning gold medal, imprinted with three soldiers performing their radio duties, was Fond du Lac chairwoman Karen Diver, who told the Duluth News-Tribune, “We’re delighted to find out about Lex’s role and we’re proud of his efforts.”

A special ceremony will be held in Lex’s honor at a powwow in Fond du Lac. The Porter family will once again gather for that event.

The trip to Washington, D.C. was filled with meaning for the family, starting with a reception for the Code Talkers’ families at the Smithsonian American Indian Museum and including a tour of the Capitol, a visit with Congressman Rick Nolan, and to the ceremony itself. Freedom Porter said the reception the family received was overwhelming. “When people asked why we came to Washington and we told them, they wanted to shake our hand. It was really touching,” he said. “We’re so proud of my grandpa.”

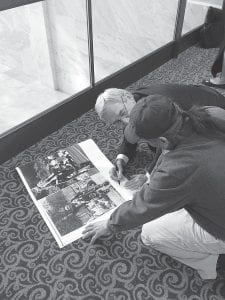

Freedom Porter said the silver medal will not be displayed in a museum. Instead, Joe Porter plans to take the medal to powwows around the region. Freedom explained, “My grandpa was an avid traveler of the ‘powwow trail.’ Joe plans to take it on the powwow trail through the summer, to tell grandpa’s story.”

Leave a Reply