In a winter the likes of what most contemporary Midwesterners have only heard of in the recollections of elders, a lone wolf ’s journey reminds us of how the people and animals of Gichi Onigamiing (Grand Portage) have always been connected to Minong (Isle Royale).

“Isabelle,” apparently cast out by the other wolves on the island, set out in late January. She traveled over a newly formed ice bridge on Lake Superior, from Isle Royale National Park to Grand Portage. She was guided on her journey by her instincts including a keen sense of sight and smell.

The ice bridge Isabelle used was created by an unusual combination of meteorological forces that have become more infrequent in recent years. It takes both cold weather and calm winds “to make” and keep Lake Superior ice. The path Isabelle took over the newly formed ice bridge followed a historic route, used for centuries by any and all traveling between Grand Portage and Isle Royale over ice or open water; by foot, dogsled, or boat.

Ojibwe families have traveled this route to Isle Royale for more than 200 years to hunt, gather, and later work for commercial fisheries, copper mines and resorts. The earliest written record of human travel between Grand Portage and Isle Royale is by John Tanner (an adopted white man) traveling in a birch bark canoe with an Ojibwe family to Isle Royale in 1794. While there they hunted caribou, otter, beaver and fished for sturgeon.

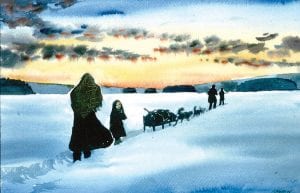

In years past, it was commonplace to cross the ice from Isle Royale to Canada or Grand Portage by dog team. The 14-mile journey over the ice bridge would have taken a four-dog team approximately three to four hours by toboggan. Usually, one person took the lead, making a trail, three to five dogs completed the team, and another person in back controlled the load. A wolf could travel the same route in less than half the time.

Imagine how some of Isabelle’s ancestors might have quietly watched as the parents of a 12-yearold Ojibwe girl, named Josephte Aiakodjiwang, who had died on the island, transported her back by dog team over the ice on February 21, 1857. These same wolves were also likely wary of the Ojibwe mail carriers making the trek to the island by dog team to deliver mail and supplies to the mining operations on the island in the 1870s. But the ice did not always hold. Three mail carriers were lost bringing the mail back from Isle Royale to Grand Portage in this same time period.

Isabelle’s journey ended in Grand Portage where she died of unknown causes. She was discovered by a local girl, Alyssa Spry, age 11, on February 8, 2014 as she played near the frozen beach on Grand Portage Bay. Alyssa’s father, Chad Spry, explained to his daughter that the collar that identified Isabelle to her young eyes as likely someone’s pet, was actually a tracking device used on wolves to learn more about how they live.

Isabelle’s story resonates with the people of Grand Portage. Her journey on a cold winter’s twilight reaffirms their connection to Minong, a pivotal part of Grand Portage Ojibwe culture and life ways. Less ice on the Big Lake makes the immigration of wolves to the island less likely. As there is less ice on the lake, seemingly, the island has moved farther away from Grand Portage.

Leave a Reply