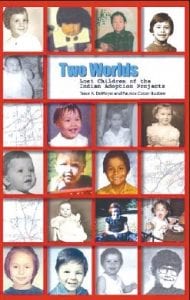

An estimated one-third of North America’s Native American and First Nations children were separated from their families by the governments of the United States and Canada between the 1940s and the 1980s. Many of them were adopted by white families and left without access to information on their medical histories, biological families, tribal affiliations, or cultural heritage. Two Worlds: Lost Children of the Indian Adoption Projects, edited by Trace A. DeMeyer and Patricia Cotter-Busbee (Blue Hand Books, Greenfield MA, 2012) is an anthology in which adoptees describe how this affected them.

The book is filled with personal stories and information on government and social practices that have been detrimental to Native children and communities. It also highlights the richness of Native culture and celebrates its strength and resiliency.

The removal of thousands of Native children took place under numerous organized efforts including the Indian Adoption Project in the U.S. between 1958 and 1967 and “the ’60s Scoop” in Canada between the late 1960s and the early 1980s.

According to Joan Black, quoted from Windspeaker Magazine, “Large numbers of Indian children were removed from their homes, often as a result of distorted suppositions of Children’s Aid Society workers about what constitutes adequate parental care and supervision in a culture unlike their own.”

According to Mary Annette Pember, who tells her own story in the book, “Before the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act that gave tribes jurisdiction over their own families, thousands of Indian children who entered the social services system were adopted into non-Indian families. Churches and social service agencies mistook Indian culture as the culprit in the community’s problems; therefore, all things ‘Indian’ were to be stamped out. Language, culture and the Indian tradition of child rearing that includes extended family were viewed as backward and wrong.”

The book traces the adoption of Native children into white families back to colonization, which has historically pulled indigenous cultures apart while taking over lands and resources. Cultures that colonize “usurp sovereignty and attack spirituality,” according to National Indian Child Welfare Association Director Terry Cross. “The last item is removal of children to educate them in the language and worldview of the colonizer.”

Many Native adoptees have tried to find their biological families but have been told they are being ungrateful for feeling a need to get in touch with their heritage, even though genealogical research is accepted among non-adoptees.

Some have succeeded in finding their families but don’t feel they totally belong in the Native world. They wonder if they are “Indian enough.” Editor Cotter-Busbee says, “I feel like I am between cultures. How do I bridge them? How do I reclaim what was lost? …How do I connect with other Native Americans? …How do I take myself out of the role of outsider? How do I heal the wounded child that keeps peering through the window of the candy store?”

Others have not been able to find their families and don’t even know what tribe they came from. “Many of these Lost Birds, as we are called, are suffering because of their plight in not finding their Native families,” says one adoptee who goes by Diane Tells His Name. She says this total disconnection from tribe and family leaves people feeling lost and incomplete. “For a Native, that is like being dead. You have no roots, no beginning, no stories, and no future.”

Some who know what tribe they came from have had difficulty getting enrolled. Others have even had difficulty obtaining government-issued identification cards because they cannot access their original birth certificates.

In 1974, Association of American Indian Affairs Executive Director William Byler testified before Congress, saying that while children were being removed from homes that struggled under “difficult circumstances” such as joblessness or alcoholism, taking them away permanently was decreasing any incentive to overcome the difficult circumstances.

An adoptee named Evelyn Red Lodge says, “Now the supreme wonder why our culture is so stricken with sadness, and I think [photojournalist] Aaron Huey described it best when he said, ‘The last chapter in any successful genocide is the one in which the oppressor can remove their hands and say, “My God, what are these people doing to themselves? They’re killing each other. They’re killing themselves while we watch them die.” This is how we came to own these United States. This is the legacy of manifest destiny.’”

Terry Cross calls the problem “historical trauma” and says the pain cannot be cured with “quick-fix programs.” He calls for more self-governance and the restoration of balance by looking holistically at the problems and not just trying to apply separate solutions to individual problems.

Writer Stephanie Woodard talks about how Indian Country is recovering from this trauma. “Now, …we Native people are remembering our traditions and remembering our communities. We’re healing from within.”

Two Worlds: Lost Children of the Indian Adoption Projects includes a chapter by adoptee Susan (Smith) Fedorko, whose biological mother was supermodel Cathee Dahmen, who was from Grand Portage. She has published a book entitled Cricket: Secret Child of a Sixties Supermodel (Outskirts Press, Parker, CO, 2013).

Loading Comments